Imagine that your quality of life depended on a specific medication — and due to a government shortage, you didn’t have access to it anymore. That was Adán Maciel Villaverde’s reality in 2017, when the government unexpectedly kicked him off his health care plan and ceased supplying his antiretroviral HIV medicine. Little did Villaverde know that his medication shortage would ultimately thrust him into an important activist role within the cannabis legalization movement.

Unsure of where to turn, Villaverde connected with doctors who were knowledgeable about cannabis thanks to Club Cannábico Xochipilli, a marijuana users’ rights group. The doctors informed him that in the absence of prescription medication, weed would stimulate his immune system. After years of using the plant to alleviate nausea, loss of appetite, and other symptoms caused by his HIV meds, Villaverde was relieved and gratified to learn that medical professionals also believed cannabis could aid his condition.

Recognizing cannabis as a treatment to ease HIV/AIDS symptoms is uncommon in Mexico. The symbiotic relationship between the seropositive rights and weed legalization movements isn’t implied the way it is in the US — specifically California, thanks to the work of activists like Dennis Peron and Brownie Mary. It’s interesting, considering how much momentum the Mexican cannabis movement has gained over the past few years. Similarly, there’s a powerful HIV/AIDS activist movement in the country, too. It’s driven by people living with the virus and many credit the movement for keeping infection rates low in Mexico, a so-called “developing country.” But few from Mexico’s cannabis legalization and HIV/AIDS rights movements have thought much of the connection.

That may seem odd to people in the United States where, comparatively, cannabis activism gained momentum through the AIDS epidemic in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Americans regularly utilized the plant to battle the virus’ symptoms and side effects of medications. Investigations — such as those conducted by San Francisco cannabis and HIV specialist, Dr. Donald Abrams — suggest that cannabis can help relieve nausea, lack of appetite, muscular pains, and psychological distress that seropositive people often experience. Other doctors suggest we need more research, however. But, studies on the benefits of cannabis for seropositive patients are not widely known in Mexico, despite the work of a handful of doctors exploring cannabis medicine, like Raúl Porras of the Mexican Council of Cannabis and Hemp [CMCC] and Rubén Pagaza of the Academy of Cannabis Medicine [AMEDCANN].

Knowing how well cannabis and HIV/AIDS activists have worked together in history, it begs the question: Could a synergistic union between HIV/AIDS patients and cannabis activists in Mexico serve to push forward national medical marijuana legislation? And could it bring another layer of healthcare to those living with the virus in Mexico?

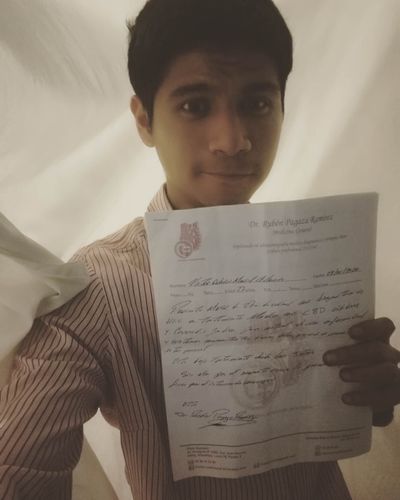

Adán Maciel Villaverde with cannabis prescription (Photo courtesy Adán Maciel Villaverde)

Some people think so. Determined to widen access to the plant for seropositive patients, Villaverde became the secretary of the Ananda Foundation, the medicinal branch of Club Cannábico Xochipilli. For years, Xochipilli operated a legal assistance hotline for members in case of police abuse, a smoking lounge in central Mexico City’s Condesa neighborhood, and helped members find access to medicinal cannabis products through Ananda.

Needless to say, Villaverde was dedicated to the cause. So, when he got a job as project director for Agenda LGBT, a decades-old, national queer rights nonprofit, he could not believe that the group’s seropositive general director Alejandro Sandoval Orci held outdated beliefs on cannabis use. “He was super against it,” says Villaverde, laughing a little at his boss’ old vehemence.

“For me, cannabis users were people who didn’t have a focus in life,” says Sandoval in a phone interview with MERRY JANE. “Obviously, that kind of perception changes when you begin to get to know the subject and the people who defend the subject.”

Sandoval had multiple reasons to learn about cannabis, however. In conjunction with his seropositive status, he also had a 66-millimeter glomus tumor on the carotid vein in his neck, which doctors suspected was related to the virus. Villaverde connected Sandoval to doctors who recommended a regimen of anti-inflammatory cannabis tinctures. Within six months, Sandoval says his tumor shrunk to 10 millimeters, and the intense headaches and muscle tension also caused by the tumor faded.

“Traditionally, the movement that advocates for the rights of people living with HIV, the LGBT or queer movement, and the legalization movement — these are movements in which many people know each other and exist in a parallel manner,” says Aram Barra, a human rights activist who works for Open Society Foundations. He is a rare Mexican activist in that he has experience with both HIV/AIDS and drug issues. Barra’s petition for an injunction (or, a judicial order prohibiting the enforcement of a government policy) from the federal health commission to consume and cultivate marijuana led to a historic Supreme Court decision that made cannabis consumption a constitutional right in 2018. “But there’s no exchange of ideas, support, strategies [between the HIV/AIDS and cannabis movements] that should be obvious, or, it seems like it should be obvious, but it hasn’t turned out like that.”

Villaverde agrees that there is an unfortunate division between the movements. “There’s a lot of discrimination from the world of cannabis towards LGBTQ people, just as much as from the LGBTQ movement towards cannabis users.”

The fact a nonprofit director who works on HIV/AIDS issues was unaware of the plant’s utility for the seropositive community is striking, considering how important HIV/AIDS activists have been in the global cannabis legalization movement.

Take Mary Jane Rathburn, better known as “Brownie Mary,” for instance. She baked infused brownies and gave them to people suffering from AIDS while volunteering at San Francisco General Hospital’s AIDS ward. Famous cannabis activist Dennis Peron also existed at the intersection of the cannabis and HIV/AIDS movements. In fact, he even opened a dispensary called San Francisco’s Buyers Club in 1992 after losing a lover to the virus. The club was the first public cannabis clinic in the United States, and it served thousands of customers on a weekly basis until law enforcement shut it down in 1996. Cops were hoping to sway public opinion away from the cannabis movement by raiding the storefront, but the opposite actually happened. One month later, California voters legalized medicinal marijuana with Proposition 215, the first legal framework for medical cannabis in the United States.

Although some medical patients have received government injunctions to legally consume cannabis on an individual basis, Mexico’s first medicinal marijuana regulations were released in January. But, they effectively restrict access to corporate pharmaceutical cannabis products only, which are often too expensive for many Mexicans who need marijuana for medicinal purposes. The regulations also prohibit smoking and all home cultivation or processing, which forces many patients to resort to the illegal market.

Biktarvy is a common antiretroviral medication in Mexico (Photo by Caitlin Donohue)

There’s overlap between the pending adult-use and current medicinal cannabis regulations in Mexico, however. If passed, recreational weed legalization will widen access for everyone, including medicinal patients. The recreational law will likely grant patients more freedom — such as home cultivation and smoking — than the medicinal marijuana framework. But in effect, the existing medical cannabis regulations in Mexico do nothing for the 270,000 people living with HIV/AIDS in Mexico, a statistic provided by the government’s National Center for the Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS [CENSIDA]. (This figure also includes the 3 out of 10 seropositive Mexicans unaware of their status.) In the interviews conducted for this feature, seropositive cannabis patients said they tend to smoke weed or consume edibles to deal with their physical and emotional symptoms. Ultimately, this points to the pitfalls of legalization laws: They don’t always widen access for everyone. Furthermore, it also highlights the fact that people are going to track down the cannabis products they need, regardless of what official regulations say.

Adult-use legalization in Mexico isn’t a guarantee, however. Anti-weed stigma is common in Mexico, where a bloody Drug War has cost hundreds of thousands of lives, leaving many to connote cannabis with violence. A poll taken in January found that 60 percent of Mexico’s population opposes recreational weed legalization. Few positive — even neutral — portrayals of the drug exist in the country’s mainstream media, where a long-running television drama series called La Rosa de Guadalupe is driven by Catholic morals and promotes alarmist visions of what it means to ingest or sell cannabis.

Negative attitudes towards the plant make it easy to believe President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) when he alludes to initiating a voter’s referendum to reverse the Court’s support for legalization. The Christian leader essentially said he’d do this, should the push for adult-use cannabis not go according to his liking.

Activist Miguel Corral protesting in Mexico (Courtesy of Miguel Corral)

While societal stigmatization makes justice for Mexican cannabis users a dubious prospect, negative perceptions about HIV/AIDS can lead to preventable deaths for seropositive Mexicans. In June, a young man was tortured and killed at a Cancun house party after sharing his status. During that same month — the ostensible month of Pride — a Mexico City man was arrested and charged with “danger of contagion” when his partner found his HIV medication and reported him to the police. 30 of the 32 Mexican states have laws against non-disclosure of one’s HIV status to a sexual partner, and a conviction can result in a prison sentence of up to five years.

“[The Cancun murder] gives us an idea of the harsh reality in which many sectors of the population live, the things that our bodies must live through because of our diagnosis,” says Miguel Corral, a longtime LGBTQ activist member of the National Council on HIV and AIDS [Consejo Nacional para el VIH y el SIDA]. Corral is originally from Tijuana, a border town that’s become a hotspot for the Mexican HIV epidemic, along with the recently surging states of Veracruz, Campeche, and Quintana Roo. “In no moment of history have these laws been an effective way of ending HIV,” Corral says. “To the contrary, the fact that these laws exist make people hide their diagnosis, not take their treatment, and many other effects that make the panorama of the epidemic worse.”

“Criminalization — the use of criminal law, which is, in theory, the last tool of the state to control the population — never is an appropriate tool for public health,” adds Barra.

Indeed, there are signs that the Mexican HIV/AIDS epidemic — which historically, the country has kept relatively contained compared to the US and Honduras — may be growing. Recent medication shortages have been limited to specific clinics, rather than being a widespread issue. But both the president’s February 2019 defunding of health nonprofits and the COVID-19 pandemic disabled many services for the diagnosis and treatment of HIV/AIDS. New diagnoses last year dipped 49 percent from 2019 — a change that is surely not attributable to less contagion. A governmental report from 2020 found that the number of deaths related to the virus has risen every year since 2016.

Some advocates see a linkage between HIV/AIDS and cannabis activism as a tool for expanding education and fighting for patients’ rights. “I think this opens a space,” says Barra. “Especially in a post-pandemic year in which Mexico’s health authorities have dedicated themselves to learning about how pandemics work and what public health tools it has to respond — to think about; what is our new health politic in relation to sexual health, HIV, and drugs?”

For Sandoval, his education on the medicinal benefits of cannabis — and interactions with his coworker Villaverde, a proud, seropositive medicinal marijuana patient — turned him into an advocate. Last November, in what Sandoval remembers as a family-friendly event, individuals from LGBT Agenda, Club Cannábico Xochipilli, and other medical marijuana patients participated in the sowing of 100 cannabis plants along Mexico City’s central boulevard Paseo de la Reforma to raise awareness around the urgency of access to the plant.

The director of Agenda LGBT is now set on advocating for increased access to cannabis not just for other Mexicans living with HIV/AIDS, but for all kinds of patients. “As an organization, we’re beginning a new fight,” Sandoval says. “We’re going to keep growing.”