The Haymaker is Leafly Senior Editor Bruce Barcott’s opinion column about cannabis politics and culture.

When does good health news magically turn into a worrisome trend? When cannabis is involved, of course.

This past week we were treated to a master class in trend creation and data twisting by NIDA Director Nora Volkow.

The study data is “very concerning,” says NIDA’s director. No, actually it’s not.

NIDA is the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the federal agency that retains a stranglehold on all cannabis research in the US.

On Aug. 21, Volkow’s agency issued a press release claiming that marijuana and hallucinogen use among young adults reached an all-time high last year.

The following day’s New York Times gave NIDA’s claim a courtesy shine. Times health reporter Andrew Jacobs basically rewrote the press release and the copy desk topped it with this header: “Use of Marijuana and Psychedelics Is Soaring Among Young Adults, Study Finds.”

NIDA Director Nora Volkow told Jacobs she found the results “very concerning.”

“What they tell us is that the problem of substance abuse among young people has gotten worse in this country,” she said, “and that the pandemic, with all its mental stressors and turmoil, has likely contributed to the rise.”

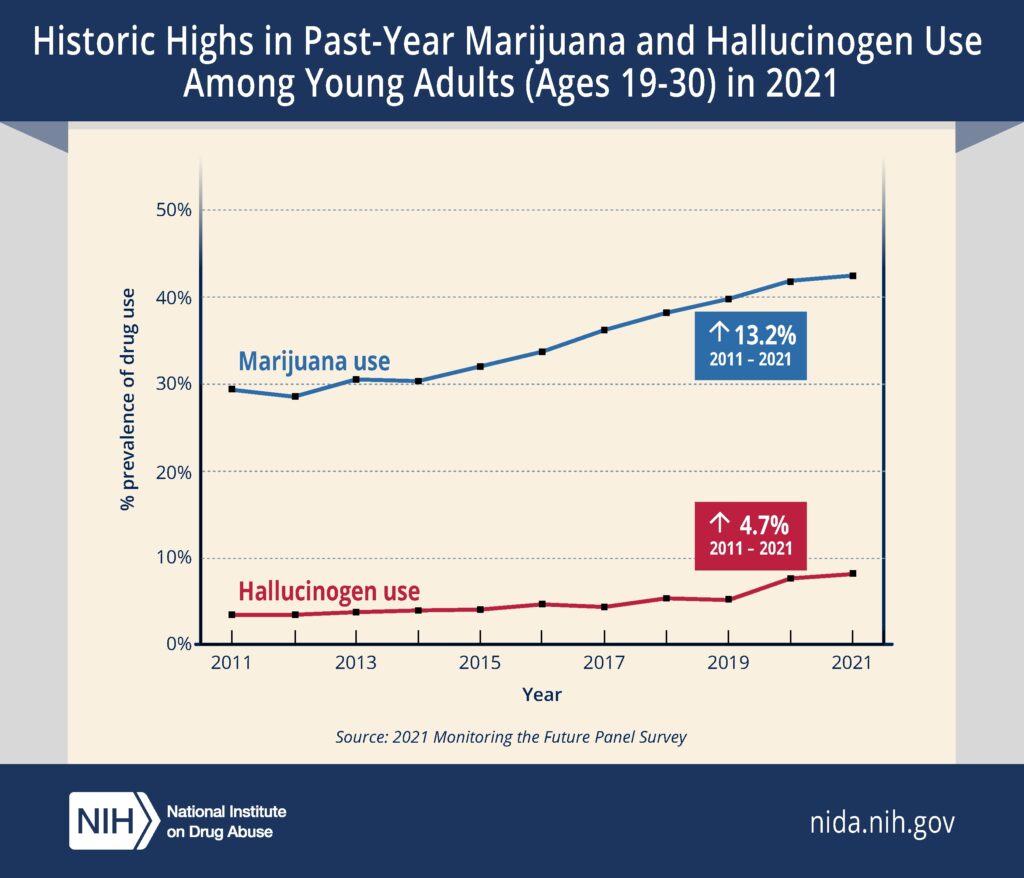

The NIDA press release included this alarming visual:

The whole thing struck me as odd. Other studies have seen a sharp drop in marijuana use among teenagers in 2020 and 2021—most likely due to pandemic stay-at-home orders that limited the opportunities for America’s teens to obtain and use weed. (I’ll leave the hallucinogen data alone for now.)

Intrigued, I took a dive into the data behind NIDA’s claim. And found—quelle surprise—a giant turd at the bottom of the pond.

Not new, not soaring, not buying it

Last week’s NIDA claim and Times headline didn’t come from a new study, it turns out. They came from the latest Monitoring the Future report, which was published last December. Monitoring the Future is a national survey of drug use that the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research has conducted annually since 1975. NIDA and its parent agency, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) help fund the study.

Legal adult use has risen as states legalize. But teen use has not increased.

Eight months ago, when that study was actually new, NIDA issued a press release heralding the survey’s finding that teen drug use, including teen marijuana use, dropped significantly in 2021. “We have never seen such dramatic decreases in drug use among teens in just a one-year period,” Nora Volkow said at the time.

The good news about teen marijuana use isn’t limited to the pandemic era. Over the past few years, as legalization has spread to 19 states, studies have failed to find a related rise in teen use. At an anti-drug conference in January, Volkow herself said she’s been surprised to see years of data that show “the prevalence rates of marijuana use among teenagers have been stable despite the legalization in many states.”

So what changed between then and now? Nothing—except, perhaps, NIDA’s need to keep the nation alarmed about cannabis legalization as election season approaches.

How do you do that when the data undermines your talking point? You rearrange the data.

Here’s how they did it: The data fudge

Pay attention to NIDA’s definition of “young adults.”

NIDA doesn’t consider a 30-year-old an adult. Age: How does it work?

When you see “young adults” in the Times headline you probably imagine people in their late teens, early twenties, right? High school and college years.

Not so.

The “soaring” use of marijuana was pulled from a data set that NIDA stretched to include all survey respondents from age 19 to age 30. Which is a ridiculously wide age range to smoosh together. At 19, you’re an idiot draining kegs and skinny-dipping in Frosh Pond. (If you’re me.) At 30, you’re married with a job, a mortgage, and a baby on the way. (Me again.)

And let’s not neglect the obvious: In legal states, 19- and 20-year-olds can’t legally buy or possess marijuana. Adults age 21 to 30 are legal.

What the data actually show

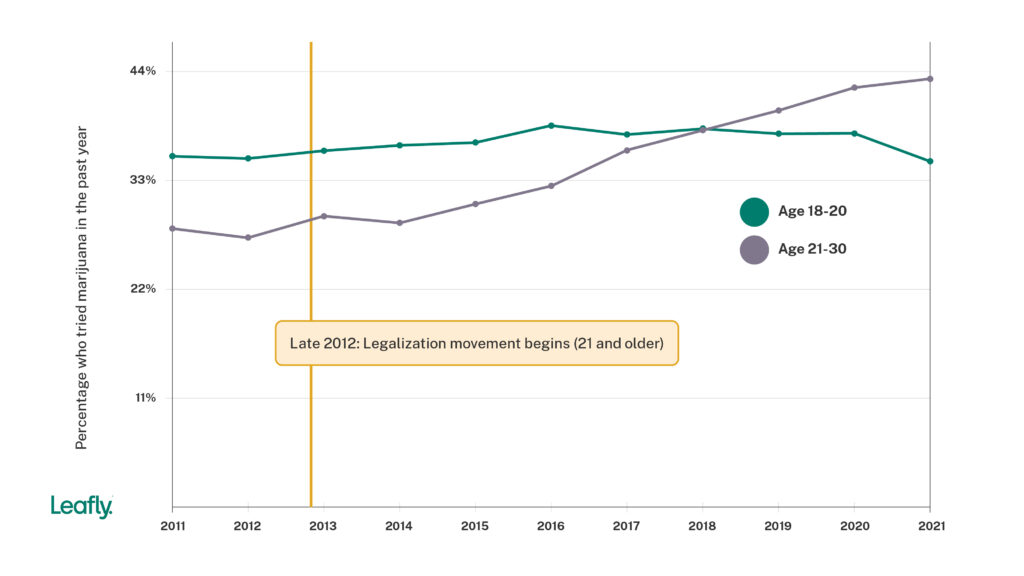

If you go into the Monitoring the Future data and separate the 18-to-20 year-olds from the 21-to-30 year-olds, you’ll find a remarkable story. (I’m including 18-year-olds because the data is there. I don’t know why NIDA chose not to use it.)

Over the past decade, as adult-use legalization has taken hold for nearly half the American population, the University of Michigan researchers found the percentage of 18-to-20 year-olds who tried marijuana at least once in the past year has remained almost unchanged: 35.4% in 2011, and 35.0% in 2021.

Meanwhile, the percentage of 21-to-30 year-olds (adults of legal age) trying marijuana increased from 28% to 43%.

Here’s what that looks like, using data from the same Monitoring the Future report:

Past year marijuana use: Underage vs. Legal Adult

By lumping the underage cohort with the legal-age cohort, NIDA dragged the average up and made it look like there was an alarming increase in “young adults” using marijuana.

Yes, more adults of legal age have tried cannabis as it’s become legal. It’s legal, and humans are curious. But in fact the percentage of underage young people trying marijuana has remained almost unchanged over the past decade.

Using key words to shape the narrative

Once NIDA’s data doctors redefined fully adult 30-year-olds as “young adults,” the agency’s director further adjusted the frame. Remember the quote she gave the Times regarding these “new” findings?

What [the data] tell us is that the problem of substance abuse among young people has gotten worse in this country.

Notice how the “young adults” in the warped data set have now become “young people” in Volkow’s summary.

Take a look at that word “abuse,” also. She’s talking about (mostly) legal-age adults who have consumed marijuana at least once in the past year. In the past year. Puffing a joint or sampling an infused gummy once or twice a year, to most rational adults, hardly qualifies as abuse. I’d call it sampling. Trying. Enjoying. But in the strange insular world of NIDA, any and all consumption of cannabis is considered abuse.

NY Times: Here, let us amplify the harm

None of this would be of much significance without NIDA working hand-in-hand with the New York Times. Instead of ignoring NIDA’s press release as a tossed-off bit of reefer madness, the Times health desk repeated the agency’s claims as established fact. The editors bit on NIDA’s hook. Instead of questioning the data, the Times reporter fluffed it up with supporting quotes and warnings about the various dangers of cannabis use.

What’s the harm, you wonder?

It’s already happening. At the end of last week, the Chicago Tribune published an editorial that used NIDA’s erroneous trend to reconsider the state’s decision to legalize cannabis. “There’s now substantial evidence that demand has indeed increased,” wrote the Trib. “Massively.” The paper’s main concern was about “young adults” and cannabis billboards “fully visible to the kids in the back seat.”

Over the coming months and years, that New York Times story will be used in editorials, presentation decks, and TV ads by powerful people who want to continue arresting adults for a gram of weed. The headline is false, and it will be used to harm hundreds of thousands of Americans who suffer under unjust and indefensible cannabis laws.

Let’s talk about credibility

Perhaps the most puzzling aspect of this whole dance was the conclusion to Andrew Jacobs’ Times story, in which he gave Nora Volkow space to ruminate on the danger of overzealous messaging.

Given the normalization of formerly illicit substances, [Volkow] said public health experts needed to come up with more nuanced and thoughtful ways of communicating the potential dangers of recreational drugs that also have therapeutic benefits.

“As a society, we tend to be very categorical about these things,” Volkow said. “We say drugs are so bad they will fry your brains like an egg and then we undermine the evidence that they can be harmful, depending on the dose and the person who takes them. By making everything black and white, we lose all credibility.”

Yes. That much is true. When you make everything black and white, and warp words and data to hype a nonexistent drug crisis, you lose all credibility.

By submitting this form, you will be subscribed to news and promotional emails from Leafly and you agree to Leafly’s Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from Leafly email messages anytime.