Fatma Khaled AbdulfattahJuly 26, 2020

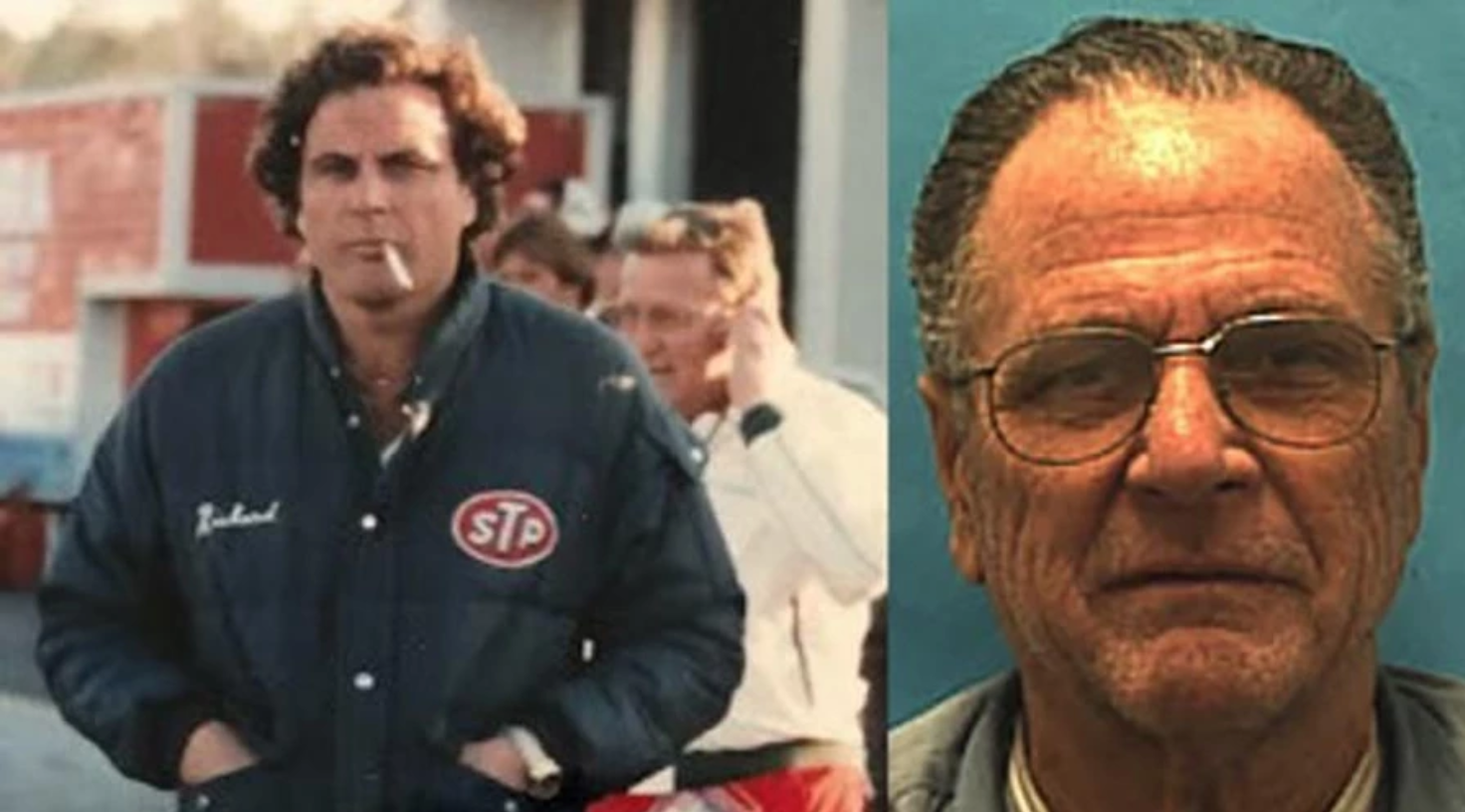

Richard DeLisi, 71, uses a walker to get around in prison. He was convicted of a crime that’s no longer a crime in 11 states. (Leafly illustration)

“I haven’t seen him in 25 years,” Ted DeLisi said about his brother Richard. “It’s really a sad thing. He is my brother. I love him. And I can’t do anything to get him out.”

Richard DeLisi, 71, is currently serving 98 years in prison for smuggling cannabis into Florida in the 1980s. He was convicted in 1989 as part of a law enforcement reverse-sting/entrapment operation.

DeLisi now uses a walker to get around Florida’s South Bay Correctional Facility. His health problems include arthritis, diabetes, neuropathy, high blood pressure, back issues, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

DeLisi is expected to be released in 2022, according to the Florida Department of Corrections. But due to his advanced age and the wildfire nature of COVID-19 in our nation’s prisons, DeLisi might not survive to see that release date. As of late July, more than 5,000 prison inmates in Florida had tested positive for the coronavirus—although that number is widely assumed to be an underestimate, due to the scarce availability of tests. 37 inmates have died of COVID-19 so far this year.

DeLisi’s friends, family, and advocates don’t want to see him become a statistic. “He is an elder in poor health and he is in a prison that is experiencing a COVID-19 pandemic,” said Chiara Juster, one of the attorneys fighting to get DeLisi released.

Richard DeLisi in the 1980s, left, and in a more recent photo, right. (Photos courtesy Last Prisoner Project)

At least 70 Americans are serving life sentences for marijuana convictions

Richard DeLisi is one of many non-violent prisoners incarcerated on long sentences for cannabis. According to the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics, one in five people currently incarcerated in the United States are in prison for a drug offense.

As of 2018, more than 70 people were serving life sentences for marijuana convictions that did not include violence. Those imprisoned include elderly inmates like Richard who suffer from medical conditions that require medical attention.

Florida voters legalized medical marijuana in a statewide constitutional amendment in 2016. In 2020, state-licensed dispensaries are expected to sell more than $800 million in cannabis products to hundreds of thousands of patients.

Meanwhile, Richard DeLisi remains behind bars for attempting to transport cannabis to Florida more than 30 years ago.

A brother’s call

His poor health isn’t the only thing weighing down Richard DeLisi these days. He gets lonely. He calls his brother Ted two to three times per day.

“I lived there [in prison] for 31 years, so I know what it is like,” Ted told Leafly. “I really want him home.”

Ted, who now lives in North Carolina, is barred from visiting his brother because prison officials believe he is a security threat. So he’s limited to phone conversations with his brother.

Both brothers were charged with the same offenses—racketeering, cannabis trafficking, and conspiracy to traffic cannabis. Ted, however was released in 2013 after serving 31 years because he appealed the conspiracy conviction. The only piece of evidence supporting the conspiracy charge was a single finger print on a map of South America. An appeals court decided that wasn’t sufficient evidence to convict him.

“I was there for 31 years for nothing violent,” Ted told Leafly. “It was just marijuana.”

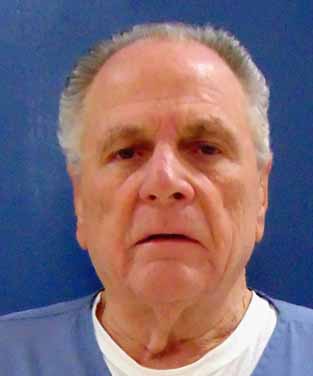

Richard DeLisi’s official state inmate photo, at the South Bay Correctional Facility near Lake Okeechobee, Florida.

98 years for a 12-to-17-year sentencing range

Sentencing guidelines recommended a 12-year to 17-year sentence for DeLisi’s crimes. Instead, he was sentenced to 98 years. Why? Because prosecutors chose to go after him on RICO charges.

The federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) was meant to be used as a tool to break the grip of organized crime on American cities. Florida passed its own state version of the RICO Act in 1977, making any criminal conspiracy a first-degree felony punishable by up to 30 years in prison.

At the time of their trial, Richard and Ted DeLisi were accused of being “orchestrators” in the state RICO Act violation for which they were charged. Because of that RICO conviction, the judge handed down a sentence that far exceeded the state recommended guidelines.

Guilty, but with an unjust sentence

Richard DeLisi’s legal team is currently gathering evidence and support for a state clemency petition. The Last Prisoner Project, an organization that helps prisoners locked away for non-violent cannabis crimes, is raising awareness about over-incarcerated people like DeLisi.

“The ‘conspiracy,’” Juster explained, which was one of the charges on which DeLisi was convicted, “was for an offense that was never completed and was entirely abandoned.”

“I’ll tell you right off, we were guilty of what they were charging us with,” Ted DeLisi told Leafly. “But we still deserved a fair trial. Richard is sitting there with an illegal sentence. If they correct it, he goes home immediately—because a second-degree felony gets a lower sentence,” time that Richard DeLisi has already served.

A sting operation set up by Florida officials

Richard DeLisi’s arrest came about as the result of a reverse-sting operation. That’s a form of entrapment described by officials at the Last Prisoner Project like this:

A reverse-sting is an operation in which the police, through covert means, target individuals who have or are likely to commit a particular type of crime. The authorities then create or facilitate the very offense of which the defendant is convicted, in this case meaning the crime was never actually committed. All that was required to create the conspiracy charge was a recorded agreement from Richard to commit the crime. It is a controversial police tactic and is deemed unlawful in many countries around the world.

An informant named James White worked with several government agencies, including the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, IRS, and customs, to essentially create a criminal conspiracy and entice the DeLisi brothers into it.

Richard DeLisi was captured on an audio recording agreeing to commit the crime. The Florida Department of Law Enforcement monitored White’s contact with the brothers for four months as they set up a deal to smuggle marijuana across the Caribbean into the United States.

The DeLisi brothers were only two of many people set up and/or arrested as a result of James White’s actions.

“Before acting as an informant, White set up at least 75 individuals who were charged with drug crimes,” said Elizabeth Buchanan, one of Richard DeLisi’s attorneys.

How injustice affects an entire family

Growing up in New York with his brothers Ted and Chuck, Richard never really learned to read and write. Severe dyslexia preventing him from gaining the skills. So he taught himself in prison. A childhood friend, Ted Feimer, sent him phonics books in jail and worked through lessons with him over the phone.

DeLisi may have learned new skills in prison, but he also missed out on all the life events that transpire in any family. Richard, Ted, and Chuck’s father passed away last year. In 2018, Richard’s daughter Ashley suffered a severe car accident in which she injured her hip. He’s never met his grandchildren in person. His two children, Rick and Ashley, grew up and matured into adulthood while he was locked away.

“I know Richard has a good heart,” said Richard DeLisi’s niece Gina DeLisi. “He is not a violent man. This is just a hard thing to live with. It’s a nightmare.”

Gina’s father Ted was locked up when she was 16 years old. That brought about anxiety that often made it hard for her to go the courtroom. Richard’s kids, she said, had similar experiences growing up.

“You have no idea the money, the energy, the anxiety, and the depression that this causes families,” said Gina DeLisi. “It’s frustrating to have your hands tied behind your back.”

What happens next

Gina DeLisi and other members of the family are working with Richard’s attorneys and advocates, posting petitions on social media, and spreading awareness about what is happening in the system—not just with their family member, but with the thousands of Americans still held captive in the war on drugs.

The legal team is hoping that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis will be made aware of Richard DeLisi’s case and grant him clemency.

How to help free Richard DeLisi

You can help by:

- Contacting Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and urging him to grant clemency to Richard DeLisi. Call (850) 717-9337 and email GovernorRon.Desantis@eog.myflorida.com.

- Learning more about Richard DeLisi and fellow drug war prisoners through the Last Prisoner Project.

- Spreading the word about Richard DeLisi via your social media platforms.

- Writing DeLisi personally at Florida’s South Bay Correctional Facility, 600 U.S. Highway 27, South Bay, Florida 33493-2233.